So, I haven't seen Pixar's new film Brave. And I'm probably not going to.

I am genuinely glad Pixar did a film that a lot of people are receiving well because of a female protagonist. I am not glad, however, that they did it while trading on Scottish stereotypes.

Or, as Graeme McMillan put it in Time: "Look at Brave with its heroine rising above the cliché of the demure, passive princess even as those in her immediate vicinity seem to have come from Celtic Cliché Central Casting."

Brave is certainly not the first film to do this. The central character of Shrek is a character who encompasses all the negative stereotypes of the Scots—grumpy, penny-pinching, misanthropic, hulking oafs. The dour Scots. (Note the irony of its being a movie about tolerance whose lead reinforces the very narratives that underlie caricatures used to marginalize Scots.) Mike Myers, who voiced Shrek, built a career on playing Scottish stereotypes: From the grumpy shopkeep in SNL's recurring "If It's Not Scottish, It's Crap!" sketch, to the Scottish dad in So I Married an Axe Murderer, to the loathsome kilt-clad Fat Bastard of the Austin Powers franchise. Every time we see a trailer for Brave, Iain grumbles: "How is Mike Myers not in that movie?"

Scottish stereotypes have shown up as sidekicks, comic relief characters, Magical Celts, and noble domestics at least as far back as Scotty on Star Trek (who wasn't even played by a Scot). One of Disney's most famous secondary characters is Scrooge McDuck, an embodiment of the stingy Scot stereotype. The Simpsons have Groundskeeper Willie. The Smurfs were updated with Scottish stereotype "Gutsy Smurf." Robin Williams cross-dressed his way into his children's hearts as Mrs. Doubtfire. Ewen Bremmer, best known as Spud from Trainspotting, often pops up as a token Scottish caricature, often with a "hilariously" impenetrable Teuchter accent, like kooky pilot Declan in The Rundown.

Dwarves in fantasy franchises are routinely made Scottish, and Scotland (along with other Celtic cultures) is frequently the backdrop for "magical historical fiction"—it is a place inhabited by dragons where wizards roam the Highlands. Or, a place where helpful Scottish sidekicks help train dragons, anyway.

And broad Scottish stereotypes are increasingly popping up in American advertising.

The point is: Brave is in good company.

Please understand: I'm not telling you not to like Brave. I'm asking you to understand it in a larger cultural context, which is more complicated than the good news about Pixar finally realizing girls exist.

Like its cohorts, Brave is doing something very cynical in its appropriation of Scottish culture for the backdrop of this film: It's using the most identifiably tribal white culture to side-step charges of racism while playing the same goddamn exploitative game of hilarious caricatures and noble savages.

Scottish people, with their clans and tartans and ubiquitous red hair, have become the go-to group for makers of pop culture who want all the fun of racial stereotyping without the charges of racism.

"Scots are tribal with weird indigenous clothing and silly instruments and some old language and funny words and goofy accent and ginger hair, and these facts have been used to marginalize this occupied nation for centuries, but they're WHITE, so it's okay!"

These are the exact things that have been used to paint reductive pictures of people of color in animated (and non-animated) films for years.

That Scots are now frequently used as "hilarious" sidekicks and broad comedic punchlines, and historical Scotland as a shorthand for "magical kingdom," and that Scots are the most identifiably tribal white culture is not a coincidence.

Whiteness is not a monolith.

Acknowledging that a universal white culture is a fallacy even though a universal white privilege is not, is an important part of dismantling white supremacy. Othering certain groups of white people isn't a part of dismantling white supremacy; in fact, it serves to reinforce the racist narrative that there is a default "normal (white) culture" from which people exclude themselves by being "different."

When people of Scottish extraction don't object to Othering, that silence is construed as tacit tolerance and used to suggest that peoples of color, particularly indigenous peoples, who object to similar treatment of their cultures are "oversensitive" and "overreacting" and all the other familiar silencing tactics.

Meanwhile, when people of Scottish extraction do object—surprise!—the same silencing tactics are used against them.

Which is all the evidence one should need to identify that it's the same gross game, in a whiter package.

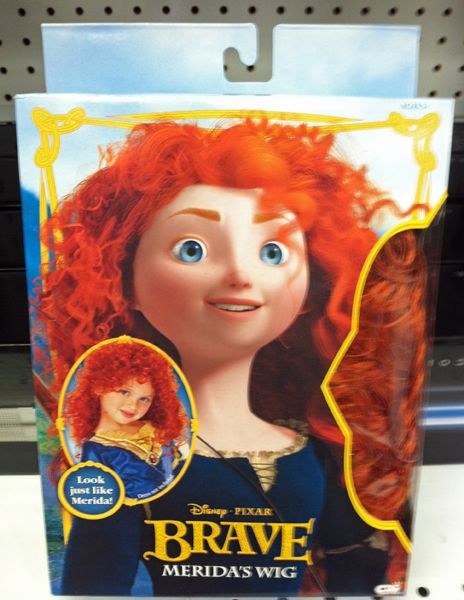

And hey—speaking of packagaing: Spudsy texted me this picture (which I am posting with his permission, along with our accompanying conversation) of a red wig being marketed in association with Brave:

Spudsy: Hey kids! You know you usually make fun of ginger kids? Well now that you think it's cool, you can look just like them with the convenience of taking it off when the novelty is gone!So much for their Strong Female Character.

Liss: It's like a fat suit for your head!

Spudsy: LOLOL!

Liss: Also: Check out the "sexy" pose of the little girl on the packaging. Come-hither eyes; chin down.

Spudsy: Exactly! The character [isn't sexualized—eyes averted; chin up], but the human kid is posed "sexily." WTF???

Who, of course, evoked the tiresome stereotype of the "fiery redhead," but, when her ginger hair is turned into a virtual fashion accessory, the girls who wear it are meant to be Jessica Rabbit-style seductresses. Because ginger-haired women are meant to be either feisty or minxy (never both), and on that generous spectrum of acceptable stereotypes for ginger-haired girls, the fictional character can be feisty, but little girls should obviously aim for minxy. Yikes.

Dundee, we have a problem.

I want to say, again, I am glad that Pixar made a film with a female protagonist. I'm glad that Pixar made a film with a Scottish female protagonist. Scottish girls need and deserve to see themselves represented as strong, as capable, as equal, as brave.

I just wish they would have gotten it with fewer cauldrons and war paint and, well, this:

There could have been a story about a modern Scottish girl who resents the pressures of her culture to give up, say, her Olympic archery dreams and settle down and get married to a suitor of whom her parents approved. (See also!) But the thing about setting this story in some magical version of historical Scotland, in addition to disappearing Scottish people of color, is that it allows the gatekeepers of the Patriarchy to keep telling themselves—and everyone else—that the lack of true freedom for girls and women is a thing of the past. A relic, like those mysterious stone arrangements erected by primitives.

To tell the story of a modern ginger-haired Scottish girl, and the intersectional oppressions she must navigate, would have been truly Brave.

Shakesville is run as a safe space. First-time commenters: Please read Shakesville's Commenting Policy and Feminism 101 Section before commenting. We also do lots of in-thread moderation, so we ask that everyone read the entirety of any thread before commenting, to ensure compliance with any in-thread moderation. Thank you.

blog comments powered by Disqus